Climate scientists have made one thing clear: Staving off the worst impacts of global temperature rise requires widespread and immediate action to minimize greenhouse gas emissions. Even still, a new report shows that the most significant of those gases are only increasing “further into uncharted levels.”

NOAA’s latest report, published on Wednesday, looked at atmospheric levels of the three most significant contributors to climate change – carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide – in 2022. All of them, the agency said, continued to have “historically high rates of growth.”

“Our latest measurements confirm that the most important greenhouse gases continue to increase rapidly in the atmosphere,” said Stephen Montzka, NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory senior scientist. “It’s a clear sign that much more effort will be required if we hope to stabilize levels of these gases in the next few decades.”

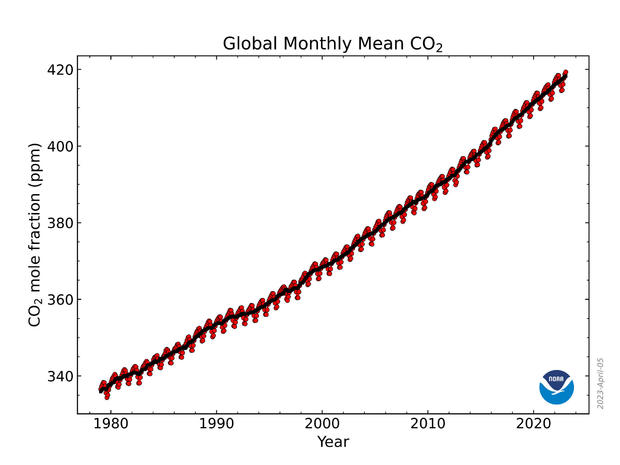

Carbon dioxide was once again of particular concern. The gas, which is primarily emitted in excess from the burning of fossil fuels in transportation, electricity and industry, rose by 2.13 parts per million in 2022 to hit 417.06 ppm. That level, NOAA said, means that the amount of carbon dioxide now in the atmosphere is 50% higher than it was in pre-industrial times.

Last year was also the 11th consecutive one in which carbon dioxide saw an increase greater than 2 ppm, marking “the highest sustained rate of CO2 increases in the 65 years since monitoring began,” NOAA said in its report.

“Prior to 2013, three consecutive years of CO2 growth of 2 ppm or more had never been recorded.”

These findings on CO2, though bleak, were expected.

The Global Carbon Project published its own report in November in which the group determined 2022 would be a “record year” for carbon emissions. They expected the concentration to be 417.2 ppm – just slightly above NOAA’s findings.

And the U.S., they found, continued to be the top emitter, with an emissions increase of 1.5% in 2022, the Global Carbon Project found.

NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory

“The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere today is comparable to where it was around 4.3 million years ago during the mid-Pliocene epoch,” NOAA said, “when sea level was about 75 feet higher than today, the average temperature was 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than in pre-industrial times and studies indicate large forests occupied areas of the Arctic that are now tundra.”

Carbon dioxide is “by far the most important contributor to climate change,” NOAA said – but it’s not the only one having a significant impact.

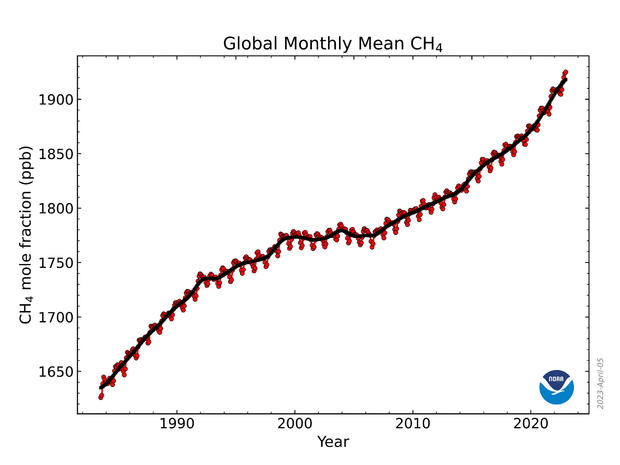

Methane, which the EPA says accounts for roughly 11% of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., has much lower concentrations in the atmosphere. It doesn’t last as long once there, but is far more potent. As explained by the International Energy Agency, it absorbs a lot more energy during its shorter lifetime, allowing it to trap more heat within the planet’s atmospheric boundaries than carbon dioxide.

Last year, methane reached its fourth-largest annual increase ever recorded, hitting an average of nearly 1,912 parts per billion – more than 2 1/2 times pre-industrial levels.

NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory

Nitrous oxide levels also saw a significant jump, rising to 335.7 ppb in 2022. That increase of 1.24 ppb from the year prior is now tied with 2014 as the third-largest increase since 2000. Most of the surplus in atmospheric concentrations for this gas are because of nitrogen fertilizer and manure used in agriculture, NOAA said.

These increases were seen in the same year that was named one of the warmest ever since record-keeping began in the 1800s. NOAA said in a report earlier this year that it was the sixth warmest, while NASEA and Copernicus ranked it as the fifth.

Combined, the increases in these three gases indicate emissions are rising “at an alarming pace,” NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad said. And even if emissions are cut down now, what’s already there “will persist in the atmosphere for thousands of years,” making it crucial to not only add to the concentration and longevity.

“The time is now to address greenhouse gas pollution and to lower human-caused emissions,” he said.